The remains of a woolly mammoth baby were once found in the frozen soils beneath a layer of permafrost, which had been untouched for thousands of years. This stirred interest around the world. This infant, named Lyuba, was preserved in almost perfect condition by the cold. It offered a glimpse into an ancient world, ruled by survival and dominated by some of the largest mammals that ever walked the Earth.

The woolly mammoth was not just a cousin of the prehistoric elephant. It was an ice-adapted master, a giant beast that shaped ecosystems during the Ice Age. Scientists and storytellers still debate its mysterious extinction.

What was it really like? How did it traverse such a vast, frozen Earth?

The Anatomy of a Giant: Waking the Baby Mammoth

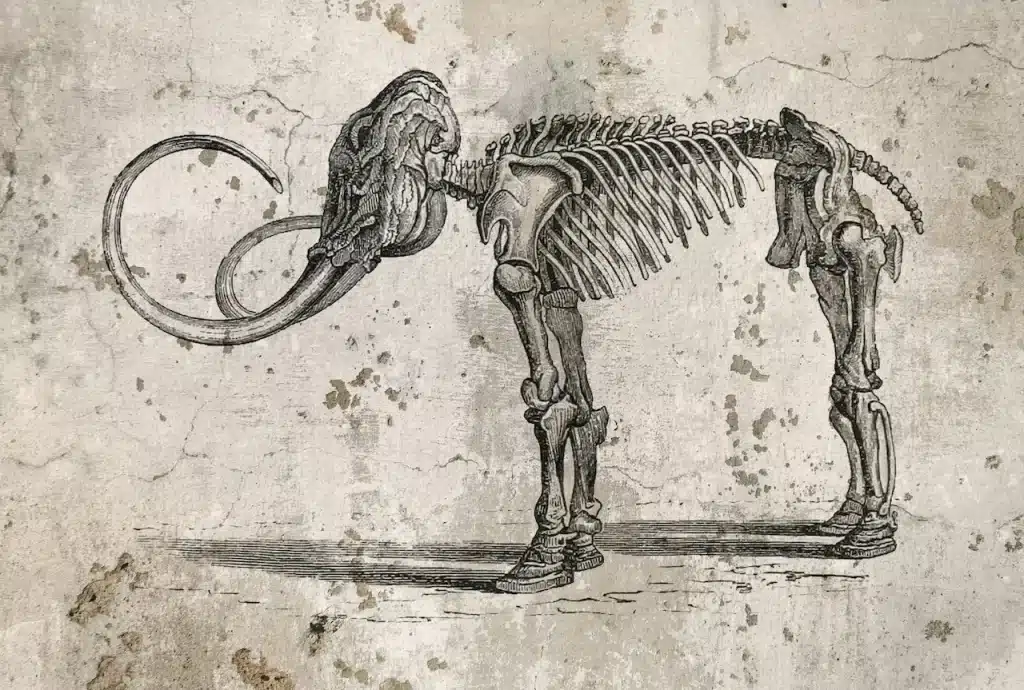

Woolly mammoths were titans of their time, standing up to 3.5m (11.5ft) at the shoulders and weighing six to eight tonnes. It was similar in size to the Asian elephants of today, but had a more compact, robust build, which was adapted for survival in harsh environments. These Ice Age giants did not live in humid jungles or warm plains like their modern relatives. Tundra wanderers.

The thick, shaggy fur was one of the most notable features of the mammoth. It wasn’t just a show, but a survival suit. The fur was made up of two layers: a coarse, long outer coat that protected them from the wind and snow, and a thick, wool-like inner layer that kept heat near their bodies. The skin of the polar bear secreted oily compounds that waterproofed their fur and provided an additional layer of insulation. Their physical features were also shaped by climate. Short ears and tails reduced heat loss, while large, curved teeth served as tools to dig through snow in order to reach the vegetation below.

The mammoth’s face was narrower than modern elephants. This gave it a distinctive profile, one that can be recognised from cave paintings in France, Spain and even deep within the Ural Mountains.

A Life in Ice: Global Range, Habitat and Range

Woolly mammoths are incredibly widespread. The fossilised remains of woolly mammoths have been discovered on almost every continent. This ranges from the cold steppes in Eurasia to frozen plains in North America. What are the only exceptions? Australia, South America, and Antarctica continents either too isolated or too ecologically unsuitable during the mammoth’s reign.

They thrived in large numbers where they were able to. Massive herds of animals moved across icy terrains, eating grasses and shrubs as well as tree bark. The mammoth Steppe was their primary habitat. This unique biome once extended from Western Europe through Russia to Canada and Alaska. This grassland ecosystem, formed by cold and dominated by hardy plants, was one of the richest biomes of Earth during the Pleistocene period.

The world was one of chilly winds, low-growing plants, and dramatic changes in seasons. The woolly mammoth occupied its centre.

Family, Society and Elephant Echoes

Much of what we understand about mammoth behaviour comes from their closest living relatives: elephants–specifically the Asian elephant, which shares a more recent common ancestor with the woolly mammoth than with its African counterpart.

Woolly mammoths lived in herds of females with their young, similar to modern elephants. These social groups were led and guided by matriarchs who helped the herd find food across the frozen expanse. After reaching adulthood, males would have likely left the herd and lived a solitary life or formed loose bachelor groups. This behaviour is reflected in modern elephant societies.

While still speculative, it is believed that reproduction followed a similar pattern: Females gave birth to one calf following a gestation of approximately 22 months. Calves would have learned survival skills in the herd, where they were nurtured over the years.

Mammoth Diet: Mammoth Teeth and Diet

Woolly mammoths had to consume a staggering amount of food every day to sustain their enormous bodies. They consumed 225 kilograms of vegetation (nearly 50 pounds) each. The main ingredients in their diet were grasses and sedges. They also ate small trees, shrubs and small trees. These plants could survive the harsh climate and nutrient-poor conditions of the Ice Age.

Mammoths had large, flat molars that were the size of shoeboxes. They were designed to crush tough plant materials. They would develop six sets of molars over their lifetime, replacing each one as they wore out. When the final set of molars was worn out, usually between 60 and 80 years old, starvation would often follow. Their teeth were like a bookend to their lives.

The Tools for Survival: Tusks & Tactics

Woolly mammoth tusks, which were elegant spirals of ivory up to 4 meters long, were more than just terrifying weapons. These tools were used for many purposes. They were multi-purpose tools.

- Remove snow and ice to find buried plants

- Protect yourself from predators such as sabre-toothed cats or packs of dire wolves

- Assert dominance among rivals during mating season,

- They could also manipulate the landscape by destroying trees or reshaping terrain, similar to modern elephants.

Recent studies have shown that mammoth tusks, like tree trunks, also store growth rings, which can provide insight into the age, health and stress levels of a mammoth throughout its life. Scientists can use these records to reconstruct Ice Age climate changes and migration patterns.

Predators and Precarity – Living on the Edge

Mammoths were not invincible despite their massive size. The Ice Age was a time when calves and weak adults were susceptible to Ice Age predators, including massive carnivores like sabre-toothed cats and short-faced bears. Humans were the ultimate and most persistent threat.

Homo sapiens spread across Eurasia around 40,000 years back. These early hunters entered the mammoths’ domain as they spread. Archaeological sites reveal that humans hunted for meat and bones. tusks and leathers. Some sites even contain mammoth bone structures–prehistoric shelters made from carefully arranged remains.

Did humans kill mammoths until they became extinct? The debate continues. Climate change and overhunting at the end of the Ice Age may have played a part. The mammoth-rich steppe was replaced by forests and wetlands that were unsuitable for the giants who loved cold weather. It was probably too much for the mammoths to handle, given that both human pressure and environmental collapse were involved.

Ghosts of the Ice Extinction and Survival

Woolly mammoths were extinct for the most part about 10,000 years ago. This was near the end of the last Ice Age. A small population of woolly mammoths survived in isolation for another 6,000 years on Wrangel Island, north of Siberia. They remained in isolation until 1650 BCE, when they disappeared.

The Bronze Age had already begun, and the Pyramids of Egypt were centuries old when they died.

Mammoths are only remembered today in the form of fossil beds, cave paintings, and DNA in frozen corpses and ancient bones. Their story is not over.

Reviving Giants De-Extinction, Ethics and Reviving the Giants

Scientists are exploring the possibility of “deextinguish” by bringing back the woolly mammoth using CRISPR gene editing and DNA from its closest living relative, the Asian elephant.

Proponents say that the goal is not to recreate Jurassic Park attractions, but rather to restore some of the mammoth-steppe ecosystem. Researchers hope that by reintroducing mammoth-like creatures to the Arctic tundra, they can slow down permafrost melting, as the animals will trample down snow and preserve frozen carbon stores.

This project raises some ethical issues: should we bring back species that we helped to destroy? What are the responsibilities that come with resurrecting an ancient species?

Legacy of a Legend

The woolly mammoth, though extinct, continues to influence science, culture and imagination. Mammoths are still recognisable in school textbooks and museum exhibits. They also appear in traditional Siberian myths, children’s books, and Siberian folklore.

It’s only fitting. The woolly mammoth was not just a giant in its day, but a symbol for resilience, adaptation and life’s amazing ability to survive even under the most extreme conditions.

Mammuthus primigenius’s legacy lives on in every frozen bone and ancient tusk, as well as in every icy grave, where baby mammoths such as Lyuba rest.

It brings back memories of a time long past, and perhaps a future to come.